Rethinking Strategy In An Age of Radical Uncertainty

Planning, Emergence, and the Wisdom of Adaptation

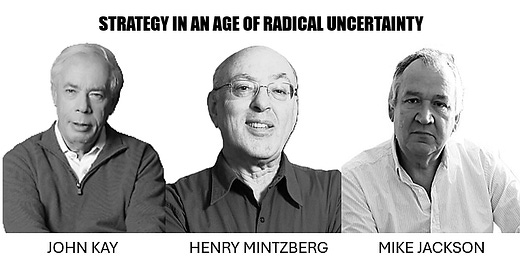

The following article is based on recently conducted interviews that Paul Barnett had with Henry Mintzberg and John Kay in advance of a very special online event on June 10th. Mike Jackson will add additional perspectives as an expert in systems thinking and practice. And they will be joined by two experienced strategists Andrew Firth and Jason Poole. DETAILS & REGISTRATION

Rethinking Strategy: Planning, Emergence, and the Wisdom of Adaptation

Featuring insights from Henry Mintzberg, John Kay, and Paul Barnett

In the shifting terrain of modern business, the limitations of traditional strategic planning have become increasingly evident. Among its most incisive critics is economist John Kay, who in his influential book Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Pursued Indirectly, argued that rigid, linear planning often fails in complex environments. Instead, he advocated for indirect, adaptive approaches to achieving long-term success.

This critique forms the backdrop for a compelling series of interviews conducted by Paul Barnett for the Enlightened Enterprise Academy, in which he speaks with both John Kay and Henry Mintzberg, two of the most respected voices in strategic thought. In Part of the interviews they explore the enduring tension between strategic planning and emergent strategy, not as a binary, but as a dynamic continuum shaped by context, leadership, and systems understanding.

John Kay: Adaptation Over Prediction

John Kay opens his discussion by dismantling the romantic myth of strategy as the product of heroic individual vision. “We have the idea that strategy is developed in what I call the ‘great man theory’ of business,” he says. “So that strategy is about the story of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs and these superhuman individuals... and I think that is complete nonsense.”

For Kay, strategy is not a grand masterplan handed down from visionary leaders.

“Strategy is emergent in the sense… of adapting capabilities of the firm to the changing market opportunities.” These opportunities, he explains, are the product of “collective knowledge and collective intelligence in ways that we can’t anticipate.”

The real work of strategy lies not in foreseeing the future better than others, but in building organizational capacity to respond to change. “Good strategy is not about foretelling the future better than anyone else,” Kay insists. “It’s about building organizations that are capable of responding to this changing and unpredictable environment.”

Henry Mintzberg: Strategy as Learning

In his interview, Henry Mintzberg echoes Kay’s rejection of strategic forecasting. As the most famous critique of strategic planning, in his book, The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, and one of the earliest and most prominent advocates of emergent strategy, Mintzberg has long argued that planning as prediction is both unrealistic and restrictive.

He criticizes the “hyper-analytical” approach of traditional strategy models, particularly those associated with Michael Porter.

“Strategy is learning, not planning,” he says. “If strategy is planning, then you want to predict what’s coming, and you can’t predict what’s coming.”

Mintzberg illustrates this point with his now-famous example from IKEA, where the flat-pack business model didn’t come from a strategic plan, but from a practical problem: “Somebody in IKEA tried to get a table in his car and it didn’t fit, so he took the legs off. And then lo and behold, somebody said, ‘Hey wait a minute, if we have to take the legs off, so do our customers.’” That small act of ordinary creativity, not a strategic blueprint, revolutionized IKEA’s global business model.

For Mintzberg, strategy emerges from the ground up, from real experiences and organizational learning. “An innovative organization looks for these little tiny clues that could lead to massive changes in strategy.”

He argues, “It’s synthesis, not analysis.”

Paul Barnett: Strategy as Judgement in Context

Bringing together the perspectives of Kay and Mintzberg, Paul Barnett argues for a more nuanced view, one that recognizes both the value of planning and the necessity of emergence, depending on the degree of predictability.

“It’s not all about emergence and it’s not all about planning,” Barnett observes. “It’s really a combination of the two.” The deciding factor, he argues, is the degree of predictability.

“The extent to which planning is either wise or foolish depends on how predictable the matter is,” he says. “And the capability to determine what is and isn’t predictable is a skill many seem to lack.”

“In other words, strategic judgment depends on being able to see clearly what is stable, what is changing, and what is unknowable. That requires not only managerial insight but systems thinking, the capacity to understand complexity, interdependence, and unintended consequences.”

Barnett’s concern is that too few leaders are trained to think this way. “Most people in organizations are trained in silos,” he warns. “They learn specific disciplines, marketing, finance, operations, and then lose sight of the interconnections between them.”

“Cognitive fragmentation makes it difficult to develop strategy that is either truly emergent or sensibly planned.”

Where They Agree: Emergence as a Strategic Imperative

Despite their different emphases, all three thinkers converge on several critical insights:

Planning has limits. Predictive strategic planning, while useful in certain contexts, fails in the face of rapid change and complexity.

Emergence is essential. Strategic success depends on the organization’s ability to learn, adapt, and respond to unforeseen developments.

Scenario planning is a thinking tool, not a forecast. Kay notes that when people engage in scenario planning, they often ask, “So which of these is going to happen?” To which his answer is, “None of these is going to happen.” Scenarios are useful only insofar as they stimulate broader thinking and help build adaptive capacity.

Strategy is more about process than plan. Mintzberg and Kay emphasize that strategy should be viewed as a dynamic, evolving capability, not a fixed destination.

Conclusion: Toward a More Enlightened Practice of Strategy

What emerges from these conversations is not the end of planning, nor a celebration of chaos. Instead, it’s a call for a more enlightened, flexible, and context-sensitive approach to strategy, one that blends planning with openness, vision with humility, and direction with discovery.

Mintzberg champions the creative potential of the everyday. Kay advocates for organizational resilience over prediction. And Barnett reminds us that the true test of strategic competence lies in knowing when to plan, and when to let strategy emerge.

Together, they invite a rethinking of strategy, not as the pursuit of control, but as the craft of navigating complexity with awareness, adaptability, and purpose.